Subscribe to trusted local news

In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever. By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

- Subscription costs less than £1 a week with an annual plan.

Already a subscriber? Log in here.

16

Dec 2023

The para athlete setting ice swimming world records and living life to the max

I meet Jonty Warneken almost 29 years to the day of his car crash. It was November 29, 1994, when he veered off a road near Ripley at 50mph, ploughed through a hedge and hit an oak tree. His injuries were so severe that his lower left leg had to be amputated.

In the years since, Jonty has taken on extreme challenges, set world records and represented Great Britain in ice swimming. So how has he done it? How does someone move on from such a traumatic incident to live such an extraordinary life?

‘I take it this is a fatality’

Jonty was 22 years old on that day in 1994, driving home alone from a job interview in his 1963 MGB Roadster. It didn’t have seatbelts and, like many classic cars, wasn’t the safest of vehicles, even by 1990s standards. It took emergency crews an hour to cut him free. After he arrived at the hospital, a police officer who’d been at the scene of the crash entered A&E saying, ‘I take it this is a fatality.’

Jonty spent six months in hospital. As well as facial injuries which would require his nose to be rebuilt, both his legs were badly damaged. His left leg later became infected. He was given a choice: five operations over three years for a 30 per cent chance of being able to use it again, or amputation below the knee. He chose the latter.

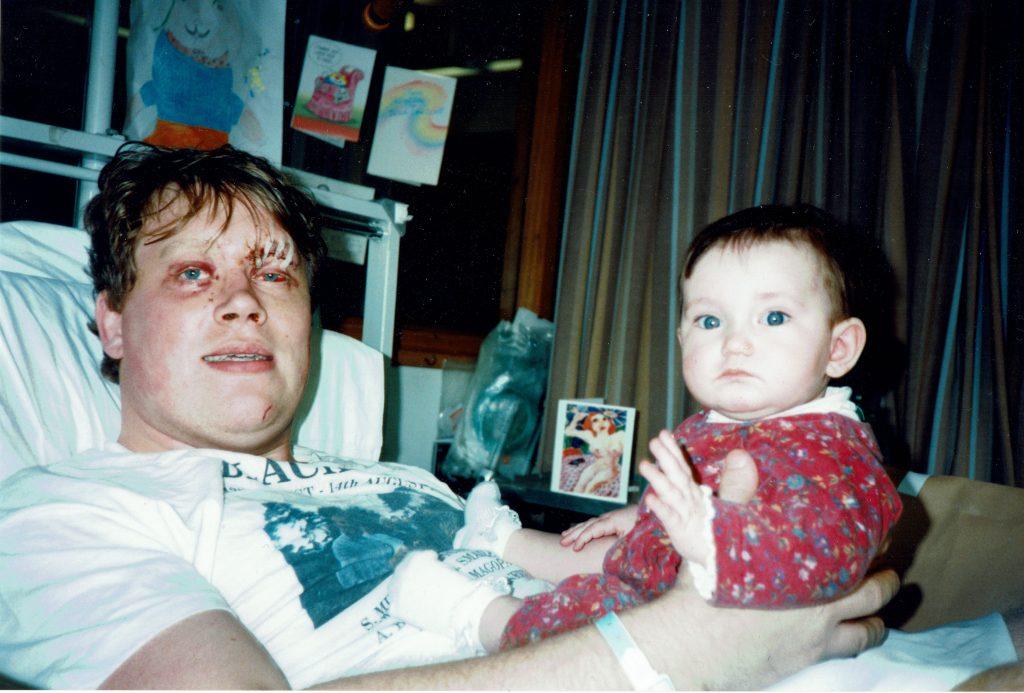

Jonty in hospital after the car crash

He remembers sitting up in bed after the operation and looking down at the space under the duvet.

First up, he wanted to do everything he could to make sure he wasn’t a burden and a worry to his family and friends. Secondly, he wanted to be out of hospital as quickly as possible - something he managed on June 5th, his mother’s 50th birthday and just two weeks after the amputation.

He set himself more goals. He wanted to be walking as best he could by the time of a friend’s wedding in July, around six weeks after the amputation. By the end of that year, he’d got a job.

A commonality of suffering

Now 51, Jonty discovered open water swimming 12 years ago, when his brother Andrew decided to give it a go and asked him along. They had grown up in Nidderdale and spent many happy times as children swimming with their friends in local rivers, but Jonty was surprised how much he enjoyed it again. It was easier on his leg than other activities, and he loved being in nature, which he describes as “the best balm for my mind and soul”. He now lives near Wetherby and promotes accessibility to the outdoors as a trustee of Open Country, a Harrogate charity that helps people with disabilities to access and enjoy the countryside.

Open water swimming led to ice swimming (swimming in water under five degrees) and the start of some extreme challenges. In 2014, Jonty became the first disabled person to complete an Ice Mile swim. In June last year, he crossed the North Channel, from Donaghadee in Northern Ireland to Portpatrick in Scotland, as part of 'Team Bits Missing', the only para swimming relay team ever to do so.

Team Bits Missing with Jonty, second from left

And in September this year Jonty crossed the same stretch of water again, this time on his own, in a time of 15 hours, 22 minutes and 41 seconds. With no wetsuit on, in line with official rules, he had to contend with cold water, lion's mane jellyfish (“They really hurt “), and currents that pushed him so far off course that he ended up swimming 33-and-a-half miles instead of the 21 it should have been. He was the first amputee, and 135th swimmer overall, to complete the challenge solo.

Jonty at Knaresborough Lido, in a water temperature of one degree

'We can do this as equals'

That sense of equality is really important to him. He sees one of his greatest achievements as successfully pushing for a change in the system at the International Ice Swimming Association (IISE)’s World Championships in France. It allowed a para mixed freestyle relay team, including Jonty, to compete as a country in its own right, swimming against able-bodied national teams.

'I'm playing my hand to the max'

Before ice swimming, it was skiing that replaced rugby after the crash. He had never tried it until he heard about a trial being held by the British Disabled Ski Club. Straight away, he was hooked. And, in typical style, he’s aiming to push his limits there, too. In January last year, he had to abandon plans to ski in the Montane Yukon Arctic Ultra in Canada, said to be the world’s coldest and toughest. He’d caught Covid during preparations on an Arctic survival course in Sweden.

It’s this ‘why not’ mentality that his beloved wife, Penny, has to keep in check. She seems to be the only reason he’s ever said no to anything.

But he is beginning to recognise his limitations and the strain his body is under, particularly his remaining leg which was also badly injured in the crash.

Whether he listens to his body is a different matter, though. He’s written down some ‘rules of life’ which include: I say ‘yes’ a lot more than ‘no’ to try new things’ and ‘I accept that pain and suffering are part of what I have to go through to achieve what I want to achieve’.

So what else does he want to achieve? Still on Jonty's bucket list is a North or South Pole skiing challenge. He's aiming to get 'all the big stuff' done before he turns 65, and then he says he owes Penny the rest of his time.

I have one final question for Jonty, and it's one he gets asked often. Given that he says his disability hasn’t held him back, and that he’s met his wife and a great community of ice swimmers and friends since his accident, would he turn back time if he could?

Do you have an extraordinary story to tell? Get in touch with Katie at contact@thestrayferret.co.uk

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Read more

- The Nidderdale mole catcher: “People can be funny about what I do”

- Harrogate disability charity celebrates Yorkshire countryside

- Business Breakfast: Swinton Estate launches wild swimming lake

0