Subscribe to trusted local news

If you are accessing this story via Facebook but you are a subscriber then you will be unable to access the story. Facebook wants you to stay and read in the app and your login details are not shared with Facebook. If you experience problems with accessing the news but have subscribed, please contact subscriptions@thestrayferret.co.uk. In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever. By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

- Subscription costs less than £1 a week with an annual plan.

Already a subscriber? Log in here.

05

Apr 2025

Eight things you might not know about the Stray

The Stray is so familiar to everyone who lives in or near Harrogate that we all think we know it. But do we?

The Stray we know and love today seems eternal, but in fact it’s simply the latest incarnation of a patch of land that has been changed beyond recognition over the centuries, and been used for far more than just football and fairgounds.

Here are eight things you may not have known about Harrogate’s most treasured asset.

1. It’s not what you think it is

Think of the Stray, and chances are that you’ll have in mind the great expanse of green that curves around the town centre, punctuated by the Empress, Prince of Wales and Crown roundabouts.

This is indeed the great majority of the Stray, but there are other bits of it that you may never have suspected were parts of it.

According to the 18th-century legislation, if any part of the Stray is built on, it must be compensated for by the same amount of land elsewhere. This has happened lots of times during the Stray’s history, and as a result, there are lots of tiny, non-contiguous snippets that are legally covered by the Act.

For example, to the untrained eye, the strips of grass along Leeds Road, Wetherby Road, Otley Road and Knaresborough Road are simply verges, but in fact they are ‘slips’ – little bits of the Stray that are protected by law.

Even a small piece of land in front of the Old Swan Hotel is also part of the Stray. Until relatively recently, it was used for parking cars, but in recent years has been grassed over and looks a little more like the rest of the two hundred acres.

The patch of the Stray in front of the Old Swan Hotel.

2. It used to be moorland

Today’s green expanse of lawn is not what you would have seen in central Harrogate before the 20th century.

Originally, the land was rough and wild. One early traveller said it reminded him of a “Scotch heath”, and Dr Stanhope, who wrote a seminal text on Harrogate’s springs, said it looked like “a rude barren moore”. On his journey here in 1626, he needed the services of a guide from Knaresborough.

In 1697, traveller Celia Fiennes complained that the whole of the area of the spa was “all marshy and wette” – a condition that hasn’t changed much on some parts of the Stray.

Novelist Tobias Smollett wrote in his bestseller Humphrey Clinker in 1771 that what is now the Stray was "wild common, bare and bleak, without tree or shrub, or the least signs of cultivation”.

This changed through the 19th century, when the land was drained and stripped of its natural features “to render it more productive for grazing purposes”, and livestock was grazed on the Stray right into the early 20th century.

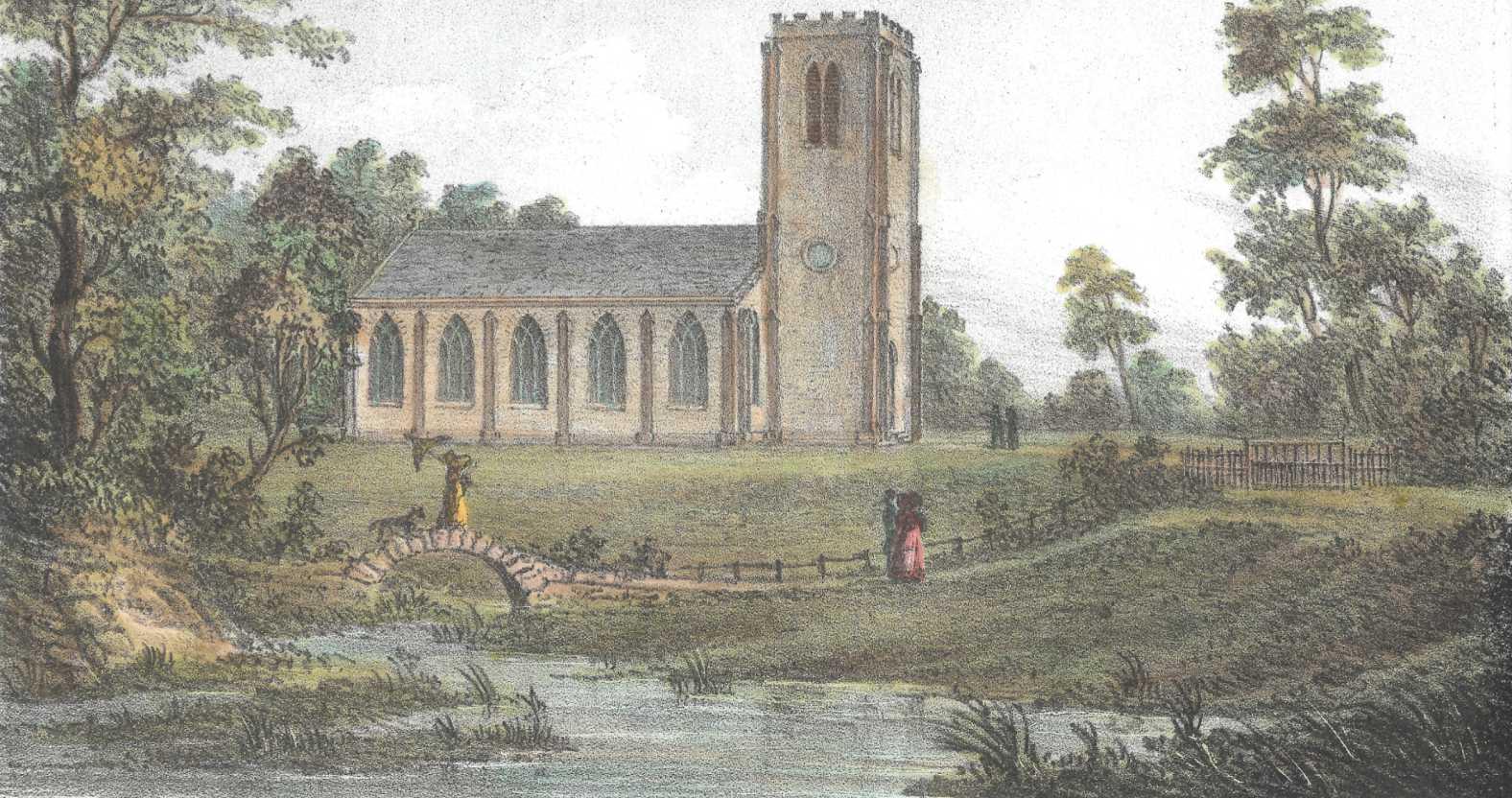

This 1829 painting shows a natural pond on what is now the Stray next to the Crown roundabout. Credit: J Stubbs.

3. It had a racetrack on it

For many years, the Stray was used for racing horses. Blind Jack Metcalfe of Knaresborough wrote that he had raced competitively on Harrogate common in the 1730s.

In fact, it became such a tradition that a racecourse one-and-a-quarter miles long was laid out in 1793.

The York Herald and the Leeds Mercury reported regularly on the Harrogate races. The late Harrogate historian, Malcolm Neesam quotes one such report in his book, Harrogate Great Chronicle:

Our race ground is at this moment crowded with horse, foot and upwards of three score carriages, to women’s horse races, pony races, women running for shifts, and men trying to catch soap-tailed pigs. In short, the place seems to be all mirth and good fellowship.

The curve of the racecourse can still faintly be seen from above in dry weather.

4. It had a railway station on it

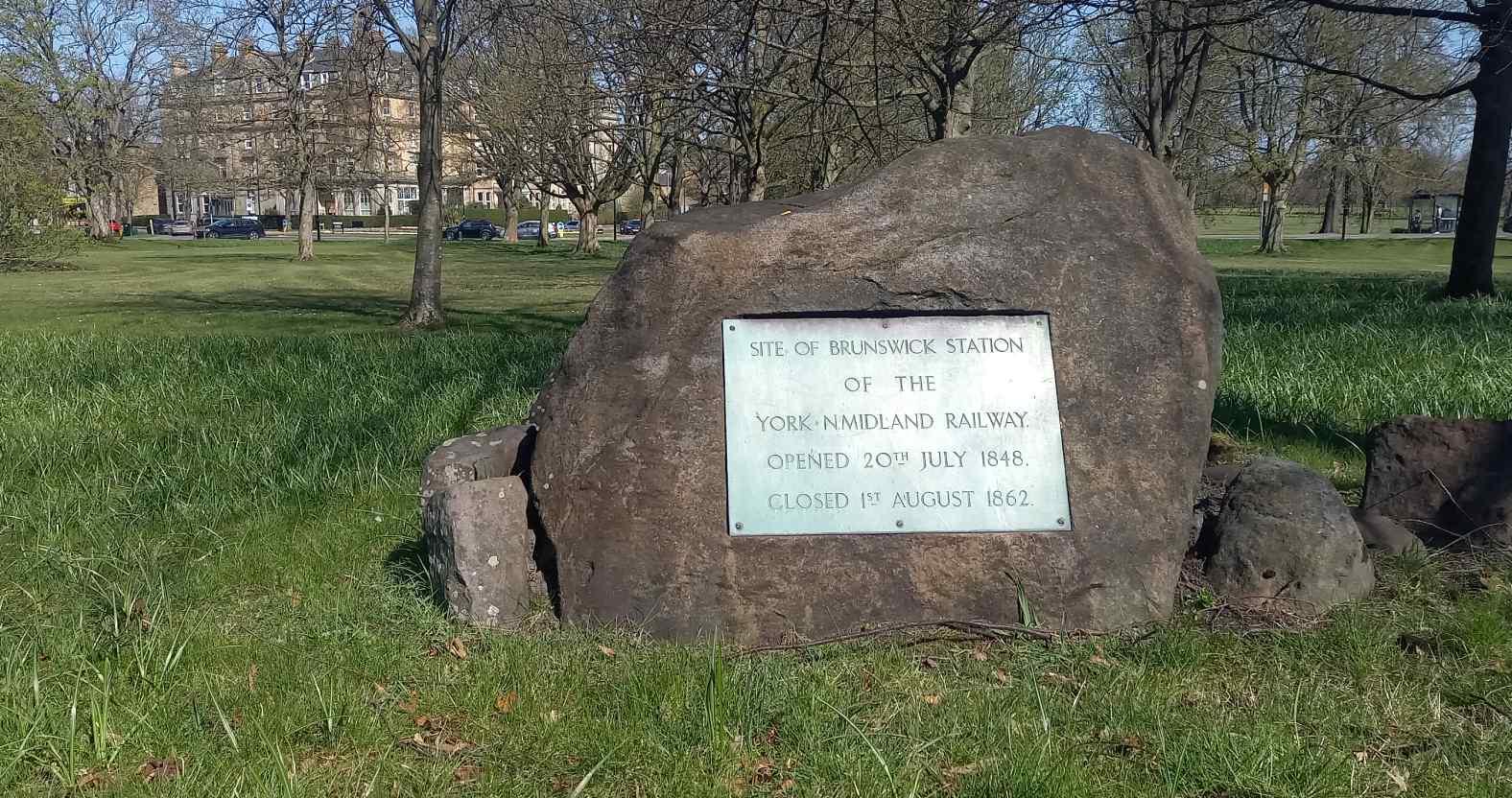

Harrogate’s first railway station was on the Stray. Brunswick Station, named after the nearby Brunswick Hotel, opened on July 20, 1848 and was the terminus of the Harrogate branch of the York and North Midland railway.

After the line crossed the Crimple Viaduct, it veered north-west just after where Hornbeam Park station is now, and passed through a tunnel under Langcliffe Avenue.

When an alternative line was proposed, the editor of the Harrogate Advertiser railed against "the idea of removing the first sod of that beautiful Stray", and objected to "thundering trains rushing across our quiet fields and pleasant footpaths”.

He lost the argument, and the line was built – Harrogate’s central station opened on August 1, 1862.

Brunswick Station was closed and later demolished, and its land was added to the Stray, as compensation for the strip needed for the new – and current – line.

The site of Brunswick Station, near Trinity Methodist Church, is marked with a stone and plaque.

5. It's been used for prostitution

One of the roads lining the Stray once had something of a reputation for prostitution.

In his book Working-Class lives in Edwardian Harrogate, Dr Paul Jennings quotes the Reverend Ogle, former vicar of Starbeck, who said in a speech praising the work of the Prevention and Rescue Home:

Many who came to Harrogate, alas! did not enjoy themselves in an innocent way.

Dr Jennings relates that there were some 25 cases of soliciting that passed through the courts during the Edwardian period, and West Park was the most frequently mentioned location.

He writes:

It looks to have been a part-time occupation. Three were described as charwomen, and one each as laundress, cook and housemaid.

Where their address was given four were from Harrogate, including two from Oatlands and one from New Park, but five were recorded as of no fixed abode.

Dr Paul Jennings and his book.

6. It's been used as an airstrip

Yorkshire Air Ambulance helicopters often land on the Stray near the hospital, but they are by no means the first aircraft to use it as an airfield.

Perhaps the most famous instance was when Harrogate accountant HL Brook broke the record for the fastest flight from Australia to England, making the trip from Port Darwin in seven days and 19 hours.

When he landed his small red monoplane on the Stray, he was met by cheering crowds, the mayor of Harrogate, and his own father, who “although an invalid, insisted on being present at the enthusiastic reception”, according to a newsreel from the time.

Harrogate accountant HL Brook and his plane on the Stray.

7. It conceals underground caverns

There are some huge underground caverns underneath the Stray, which were built during the spa’s heyday as reservoirs to hold thousands of gallons of spa water.

They fell into disuse with the decline of the spa industry, and in the 1960s and ’70s local children were reportedly warned to steer clear of the ‘Stray Caverns’.

But according to the late Malcolm Neesam, that’s not hard, as no-one is sure how many there are or where they all are, because the plans were thrown out in the 1960s.

Some of the largest caverns were filled in by the Duchy of Lancaster in 2013, but some tanks and tunnels still remain.

Some parts of the system are still accessible.

8. It was used to 'dig for victory'

The Second World War started on September 3, 1939, and by October, the Stray was being used once more to graze sheep.

Then in the following June, the council agreed to put 102 of the Stray’s 200 acres under the plough to grow crops.

The Stray being ploughed up in 1941.

Local people started to “dig for victory” – to use the slogan of the time – on allotments on the Stray along Leeds Road, the fringes of the railway line, and near the Granby Hotel and Empress pub.

Part of the Stray was used for grain production.

Several huge water tanks were installed around the town to fight fires, and one of the biggest was positioned on the Stray opposite the end of Victoria Avenue.

1