Subscribe to trusted local news

If you are accessing this story via Facebook but you are a subscriber then you will be unable to access the story. Facebook wants you to stay and read in the app and your login details are not shared with Facebook. If you experience problems with accessing the news but have subscribed, please contact subscriptions@thestrayferret.co.uk. In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever. By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

- Subscription costs less than £1 a week with an annual plan.

Already a subscriber? Log in here.

27

Apr 2024

Local history spotlight: Naomi Jacob

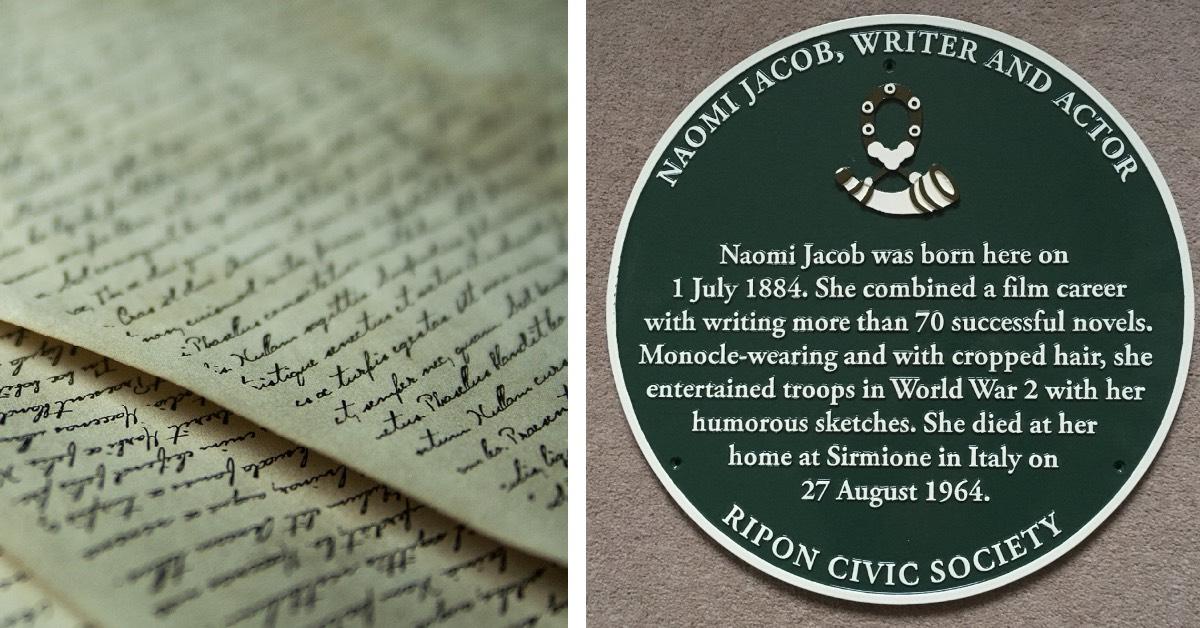

(Lead image: Pixabay and Ripon Civic Society)

North Yorkshire boasts numerous connections to the literary world across the centuries; the Brontë family immortalised Haworth and the dramatic scenery of the moors, Whitby Abbey famously inspired Bram Stoker’s Dracula, and both the television show and book series All Creatures Great and Small captured life in the Dales.

Someone who has not retained the same level of recognition – yet undoubtedly played a significant role in arts and culture at the time – is Naomi Jacob.

A prolific writer, actor, broadcaster, and political figure, she published around 50 books in her lifetime, and was known as a larger-than-life character in the circles she moved in.

Labelled 'eccentric' at the time, Jacob rarely used her given name, instead opting for her surname, Jake, or Mickie to introduce herself. She also preferred to wear what would have been deemed masculine attire, commenting: 'I just find that men's clothes are more practical and more economical'.

It was also a well-known secret that she had female partners throughout her lifetime, although this was never addressed either by her personally, or through her literary work.

Viewed through a modern lens, Jacob would have been considered part of the LGBTQIA+ community. However, because she didn’t speak about her experience, or have access to the updated language and knowledge surrounding gender identity and use of pronouns we have today, we cannot presume to know how she would have chosen to define herself.

For this reason, in the article she’ll be referred to by her surname, with she/her pronouns.

Early life

Jacob was born on July 1, 1884, in Ripon, the first daughter to Samuel Jacob and Selina Sara Ellington Collinson.

Ripon (Image: Pixabay)

Her family were fairly prominent in the town; her father was the headmaster of Ripon Grammar School, where her mother also taught, and her grandfather and great-grandfather were the mayor and chief police officer of Ripon respectively.

While her mother’s lineage had roots firmly in Yorkshire, Jacob’s father was the son of a Jewish refugee from the area formerly known as Prussia. Jacob’s paternal grandfather, whom she was very fond of, still spoke Yiddish and was a great influence in Jacob exploring her dual heritage.

Her upbringing was comfortable but her parents’ marriage was an unhappy one; when they eventually separated, Jacob moved to Middlesborough at the age of 14 to complete her education, following in her family’s footsteps to become a teacher.

While in the North East, Jacob contracted tuberculosis, and would suffer with it to varying degrees throughout the rest of her life.

A diverse and lengthy career

It also appeared that teaching wasn’t the right fit for Jacob either; the lure of the glittering lights and creative freedom that the theatre offered was tempting, and by 18 she was frequenting music halls in Leeds.

Jacob soon successfully introduced herself to some of the time period’s notable theatre alumni, including Henry Irving, Sarah Bernhardt, and Marie Lloyd. She also made a name for herself as a character actor, performing at the West End and in several touring productions.

The childhood home of the Jacob family (Image: Ripon Civic Society)

It wasn’t until the mid-1920s that her lengthy career as a writer really began in earnest. Her first novel Jacob Usher was first published in 1925 and was a prolific author during the rest of her life, able to complete two books a year at the height of her productivity.

Jacob had a deep love for Yorkshire, and this passion, and her astute observations on the region’s idiosyncrasies, were often a key feature of her novels. While she produced a vast quantity of work, sometimes under the pen name Ellington Gray, the ones she was best known for – and garnered critical acclaim – were her series about the Gollantz family, and her 1935 novel Honour Come Back.

The latter was recognised with an Eichelberger International Humane Award but Jacob refused to accept it when she discovered Adolf Hitler had also been recognised with the prize for Mein Kampf.

She penned an impassioned letter to The Sydney Morning Herald in 1936, which explained her reasons why. In an address to the editor, she explained:

While Jacob relocated to Lake Garda, Italy, in 1930 in order to alleviate some of the symptoms of her tuberculosis, she moved back to the UK during the Second World War to help with the war effort.

(L) the plaque in Sirmione (R) Sirmione (Image: Ripon Civic Society and Pixabay)

This included tapping into her acting credentials as part of the Entertainments National Service Association, to entertain the troops and keep morale high. She became well-known for wearing a Women’s Legion uniform, monocle, and sporting a cropped hairstyle.

Later in life she was a contributor to the Radio 4 programme Woman’s Hour, as well as a writing articles and opinion pieces for local and national newspapers.

Political activism

Politics was a major part of Jacob’s life, and alongside her impressive output of work she managed to be an active participant on the political stage.

A fierce proponent for women receiving the vote, she was part of the suffragette movement before World War One and joined the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU) in 1912.

According to an article published in The New York Times in 1964, she once recalled that she was frequently 'flung down steps and into horse ponds' when out campaigning. She once stood, unsuccessfully, as a Labour PPC (Prospective Parliamentary Candidate) in East Ham, London, and was a devoted Labour party member for over 35 years.

However, she actually switched sides and joined the Conservative party after 1947, citing her disappointment in what she perceived to be Labour’s more radical brand of socialism.

Later life and legacy

Jacob moved back to Italy, and to the town of Sirmione where her villa was, after the Second World War. Also known as Casa Mickie, after one of her chosen names, she enjoyed hosting friends and family there - but she regularly returned to visit England, and Yorkshire in particular.

Although she had been married to a man for a brief time - so brief in fact, that they divorced within two weeks - she had several long-term partners that she lived with in open but unspoken relationships, including the actor and singer Marguerite Broadfoote.

After she passed away in 1964 age 80, a plaque was installed in Sirmione in her honour. Jacob's vast amount of work fell out of the general public consciousness after her death, but in recent years there has been renewed efforts to preserve her legacy.

Later generations of the Jacob family at the plaque's unveiling (Image: Ripon Civic Society)

In 2019, the Ripon Civic Society recognised Jacob’s impact on not only the town but wider society, with a green plaque outside her childhood home at 20 High St Agnesgate.

Inaugurating the plaque, Christopher Hughes, Chairman of Ripon Civic Society, welcomed Jacob’s two generations of her family, Tony Atcheson and Thomas Atcheson, to the event.

He commented:

Tony Atcheson, who lived in Sirmione with Naomi Jacob and his mother as a young child, added:

Sources for this article include an article in The New York Times, an article by Jocelynne Scutt for the Women’s History Network website, the Ripon Civic Society website, a biography on LibraryThing.com, Naomi Jacob’s original 1936 letter to The Sydney Morning Herald from the National Library of Australia archive and Orlando - a University of Cambridge online anthology.

Read more:

0