16

Jun 2024

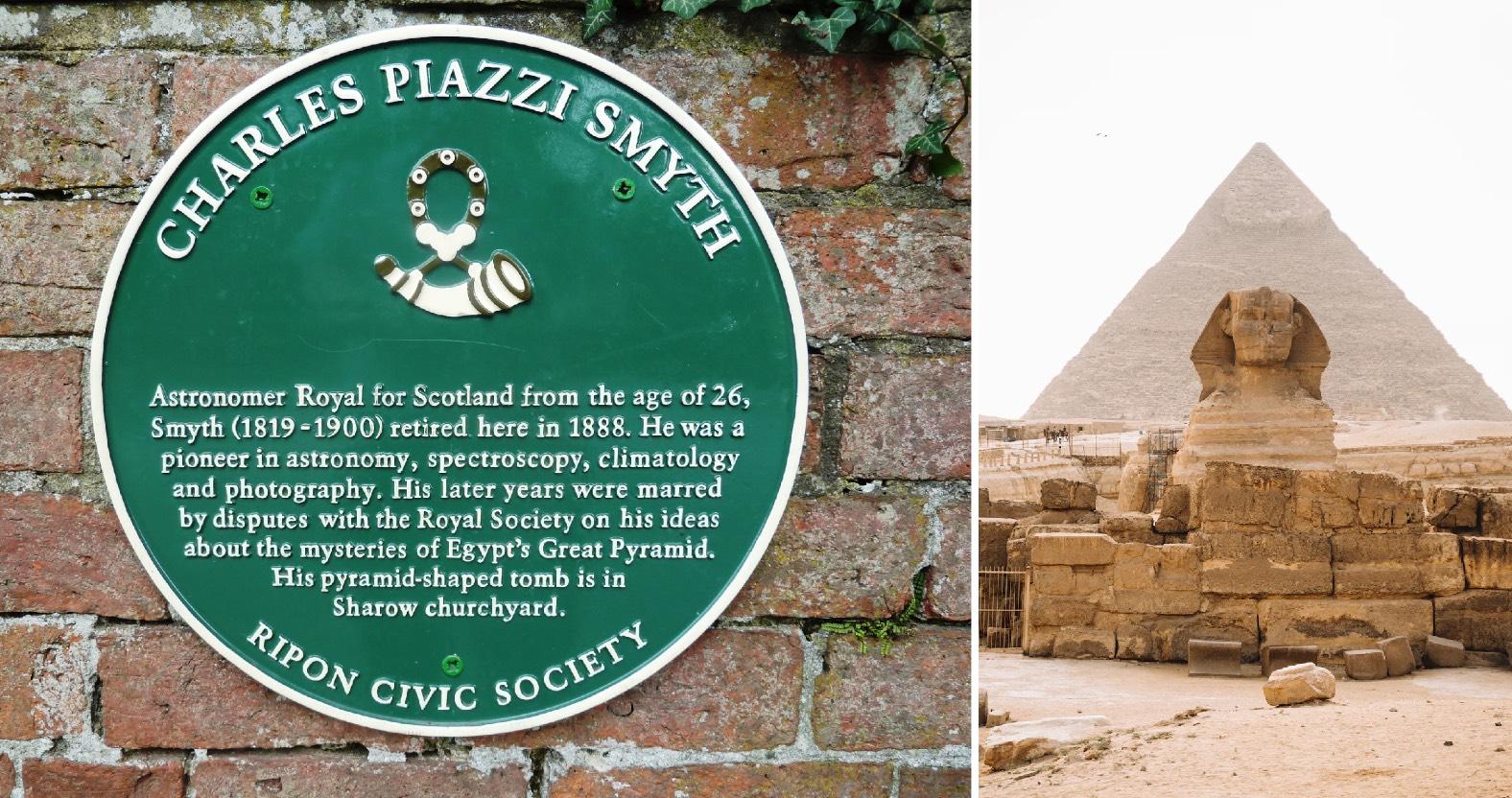

Local history spotlight Ripon: Charles Piazzi Smyth

Researching into the stories behind Yorkshire’s plaques as part of the Stray Ferret’s ongoing local history series has revealed some surprising connections across the globe.

Ripon’s relationship to The Great Pyramid in Egypt and a crater on the moon are arguably the most far-flung to date – and their existence in the first place can be attributed to one man: Charles Piazzi Smyth.

The scientist and astronomer decided to retire to Ripon in 1888, having enjoyed an extraordinary career that saw him travel around the world in the pursuit of knowledge and discovery.

Early life

Charles Piazzi Smyth was born on January 3, 1819, in Naples to British parents William Henry Smyth and Eliza Annarella Smyth, née Warrington.

His Italian middle name was directly inspired by his godfather, the astronomer Giuseppe Piazzi, a family friend who his father met while posted in Palermo with the Navy.

The adoption of his godfather’s name was an indicator of things to come – Piazzi discovered the first dwarf planet, Ceres.

In January 1801 and after the Smyth family relocated to Bedford, his father set up an observatory from which he and his son could share an interest in amateur astronomy.

This set Smyth on a path to study the stars, and at the age of 16 he was sent to the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa to take up a role as an observatory assistant to Sir Thomas Maclear. Here he witnessed many phenomena, including the Great Comet of 1843 and Halley’s Comet.

He played a key role in verifying and enhancing Nicolas-Louis de Lacaille’s findings around the arc of the meridian and became well-known for his drawings and use of photography during this time.

After nearly a decade in South Africa, he successfully applied for the position of professor of astronomy at The University of Edinburgh, quite the feat considered he would have only been in his mid-twenties at the time.

From Edinburgh to Egypt

Shortly after his appointment, the observatory on Calton Hill, was placed under the control of Her Majesty's Treasury, and he also took up the mantle of Astronomer Royal for Scotland.

Edinburgh Observatory (Image: Unsplash)

After this change in ownership, the astronomy department reportedly suffered many years of under-funding. Despite this, Smyth was responsible for installing the time ball on top of Nelson's Monument in Edinburgh, which provided a vital indicator to the ships at the port of Leith. By 1861, this was enhanced by the One O'Clock Gun at Edinburgh Castle which sounded six times an hour.

Not only was he hampered by the lack of investment, but the typical Scottish weather made visibility quite poor for studying the stars. During this time, Sir Isaac Newton proposed in his book Opticks that a higher altitude was necessary for an unobstructed view of the sky.

Taking this advice, Smyth and his wife Jessica – whom he married on Christmas Eve, 1855 – used their honeymoon to Tenerife the following year to find a location in the Canary archipelago in which to put Newton’s theory into practice.

Their findings were presented to Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty and The Royal Society in London, as well as being included in several scholarly articles.

His other scientific interests were rather more earth-bound; following the publication of John Taylor’s The Great Pyramid: Why Was It Built? And Who Built it? (1859), he become obsessed with the Pyramid of Giza, believing it to have been built by Noah from the Bible’s Old Testament – quite unusual for a man of science.

Symth's other passion was Egypt's pyramids (Image: Pexels)

In the 1860s he made the trip to Egypt to study it himself, after The Royal Society refused him a research grant. While he made many scientific observations - and is believed to be the first person to photograph the interior of the pyramid – the trip solidified his belief on many of the more outlandish religious theories first proposed by John Taylor.

Smyth published his theories in Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid (1864), Life and Work in the Great Pyramid (1867), and On the Antiquity of Intellectual Man From a Practical and Astronomical Point of View (1868) but these controversial views ultimately led to him parting ways with the Royal Society in 1874.

Retirement and rest in Ripon

After more than four decades as Astronomer Royal for Scotland, Smyth resigned from his post in 1888 and moved to a property on Clotherholme Road in Ripon with his wife.

Smyth passed the last years of his retired life in relative obscurity and on February 21, 1900, he passed away at the age of 81.

Charles Piazzi Smyth and Jessica Smyth's grave in Sharow

He was buried alongside Jessica in the village of Sharow – and his grave is certainly hard to miss. Shaped like the pyramids he became so enamoured with and affixed with a cross, the epitaph reads:

As Bold in enterprise as he was Resolute in demanding a proper measure of public sympathy and support for Astronomy in Scotland, he was not less a living emblem of pious patience under Troubles and Afflictions and he has sunk to rest, laden with well-earned Scientific Honours, a Bright Star in the Firmament of Ardent Explorers of the Works of their Creator.

As a man who spent most of his life learning about the mysteries of space, he may well have been overwhelmed to learn that there is now a crater on the moon bearing his name.

The Piazzi Smyth is a small lunar impact crater, located near a solitary moon mountain called Mons Piton, that rises to a height of 2.3km.

Back on earth, the green plaque commemorating his life is located outside of the Clotherholme Road address where he spent his later years.

Sources for this article include a post on findagrave.com, Pyramid man: Charles Piazzi Smyth published on the-past.com, a biography on the Piazzi Is Myth website, Charles Piazzi Smyth, Life and Work at the Great Pyramid, Vol. 1 (Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas, 1867), pp.293–94, a blog post on the University of Cambridge Whipple Museum website, an article on The English Library of Tenerife website, a previous article on the Stray Ferret and a post on the Ripon Civic Society website.

0