Subscribe to trusted local news

If you are accessing this story via Facebook but you are a subscriber then you will be unable to access the story. Facebook wants you to stay and read in the app and your login details are not shared with Facebook. If you experience problems with accessing the news but have subscribed, please contact subscriptions@thestrayferret.co.uk. In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever. By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

- Subscription costs less than £1 a week with an annual plan.

Already a subscriber? Log in here.

01

Jun 2024

Local history spotlight: Eugene Aram

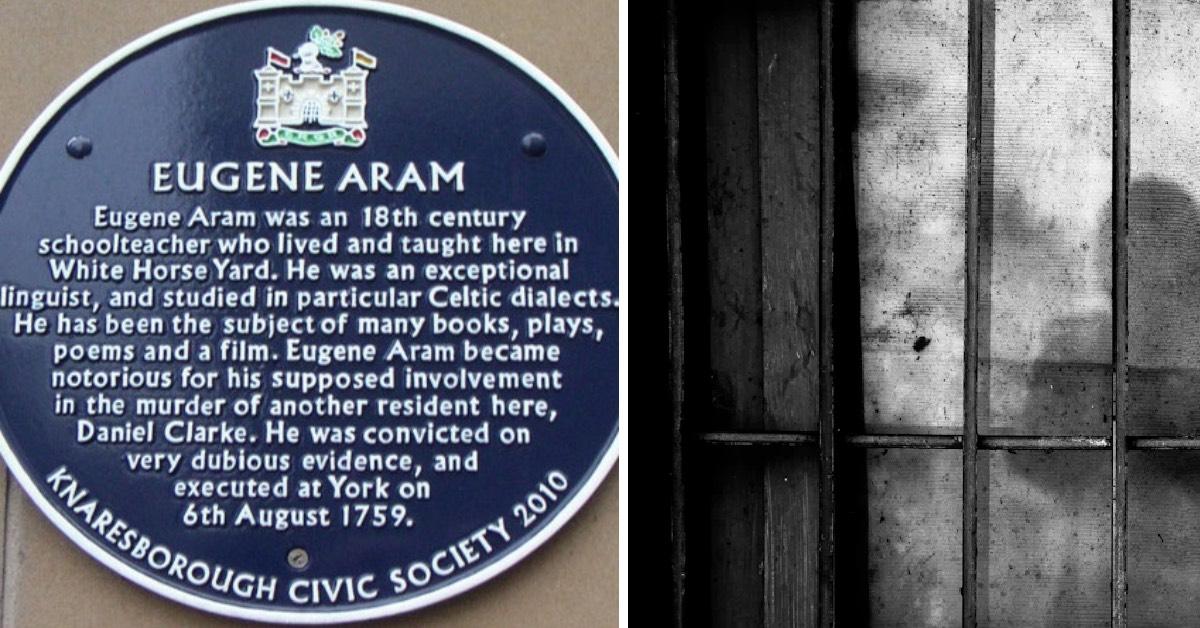

While many commemorative plaques recognise individuals that have made outstanding contributions to the local area, there are others that acknowledge those with an altogether murkier legacy.

Eugene Aram’s reputation spreads far beyond his native Yorkshire – and not just for his work as a philologist.

While he was an eminent scholar, teacher and well-known figure in Knaresborough, he has been immortalised in history as the murderer of another local man, Daniel Clarke, an allegation he vehemently denied.

With the benefit of hindsight, some have also questioned the strength of the evidence against him and his co-accused Richard Houseman.

Whether guilty or innocent, his impact on Knaresborough and Yorkshire plays an important part in understanding the history of the region.

Early life

Aram was born in 1704 in Ramsgill, West Yorkshire, to a family of humble means. His father was a gardener at the Newby Hall estate and made a modest living.

Like other children from lower-class backgrounds, Aram’s education was described only as ‘fair’ and it seemed he was destined to follow his father’s footsteps into horticulture when he also started working at Newby Hall at age 13.

However, Sir Edward Blackett, the owner of the estate allowed him to make use of the library, and Aram taught himself both Greek and Latin, falling in love with language and academia.

In 1720 he moved to London to work as the bookkeeper in the counting house run by Christopher Blackett, a relative of Sir Edward.

After suffering badly with smallpox, he moved back to Yorkshire to become a schoolteacher, first in the village of Netherdale and then in Knaresborough in 1734.

Newby Hall Gardens

During this time, he married Anne Spence ‘unfortunately’ – a commonly used phrase during this period that suggested she was pregnant with his child out of wedlock.

Married life and murder

Nearly a decade passed in Knaresborough without incident. For all intents and purposes, Aram was an ordinary family man and a well-regarded teacher.

Behind the scenes however, life may not have been quite so rosy. Aram’s marriage was far from perfect, and it seems that he may have also been looking for ways to improve his financial position too.

When another Knaresborough man, Daniel Clarke, came into money through his wife, Aram allegedly seized the opportunity.

Conspiring with his friend, Richard Houseman, they apparently convinced Clarke to purchase expensive luxury items on credit, racking up debts to many tradespeople and businesses across the town.

Shortly after this spending spree Clarke simply disappeared. Around this time, Aram – who many knew as being ‘quite poor’ – began to pay off his own debts.

Soon after this, he left Yorkshire altogether for a teaching post in London, leaving his wife and family behind, a move that caused suspicion to mount even further.

Academia and arrest

Aram managed to fly below the radar for a few years after the incident, picking up jobs as an usher in schools across England, before eventually settling in King’s Lynn.

During this time, he had perhaps distracted himself with intellectual pursuits, and produced an etymology entitled A Comparative Lexicon of the English, Latin, Greek, Hebrew and Celtic Languages.

Aram lived and taught in Knaresborough for many years (Image: Unsplash)

His writings show that he was a pioneer in the field of philology, posing that Celtic was related to other European languages, and disputing the view that Latin was derived from Greek.

His former life in Yorkshire caught up with eventually; while he was living in Norfolk unaware, developments in the Clarke disappearance were being made in Knaresborough.

In 1758, farmer William Thompson discovered a skeleton on his land at Thistle Hill. Two local surgeons inspected the remains and concluded the timeframe for decomposition fit with that of Clarke’s disappearance.

At the inquest, witnesses and new information began to paint a picture of what could have happened that night. Clarke’s neighbour William Tutin stated that he had last seen him at 3am on February 8, 1744 by his cellar door, talking to Eugene Aram and Richard Houseman before leaving with the two men.

Aram’s estranged wife Anne also gave evidence, claiming her husband had met with Houseman and Clarke that night, and that the two men returned two hours later, without Clarke. She heavily implied she believed they were both involved in the murder plot.

Richard Houseman was brought forward for questioning, and almost immediately incriminated himself.

While protesting his innocence he was said to have declared: ‘this is no more Dan Clarke's bone than it is mine’ – and his assuredness led many to suspect that this was because he knew where Clarke was actually buried.

After further interrogation, Houseman admitted that he was present during the murder, that Aram was responsible and even led them to St. Robert’s Cave, the site where he claimed it happened.

A second skeleton was actually found at the cave, and Aram was arrested in Norfolk, before being extradited back to Yorkshire to stand trial.

Aram was jailed in Tyburn Prison (Image: Pexels)

Houseman’s confession, alongside other eyewitness testimonial, was used to convict him, despite Aram’s defence mounting an elaborate and complicated argument that proposed the evidence was circumstantial at best.

Without DNA or other forensic techniques, the identity of both skeletons found while investigating the case could not be confirmed - so it could be that neither of the skeletons were Clarke's.

Nevertheless, Aram was sentenced to be hanged, and after an unsuccessful attempt to take his own life first, he died at York's Tyburn, an area of the Knavesmire used for executions on August 16, 1759.

Apparently, he confessed his guilt while awaiting his death, citing an affair between Clarke and his wife as the motive – although a supposed note left in his cell that declared himself a victim of the legal system contradicts this claim.

Legacy

The sordid details surrounding the case and the lingering questions of Aram’s guilt seems to have captured the public attention at the time and catapulted him into notoriety.

Notable references to the case in literature include Thomas Hood's ballad The Dream of Eugene Aram, George Orwell’s 1935 poem ‘A Happy Vicar I Might Have Been’, and several mentions in the fictional works of P.G. Wodehouse.

After death, Aram's skull was first acquired by the Royal College of Surgeons, before being sent to the Stories of Lynn Museum in Kings Lynn.

The Knaresborough Civic Society installed the blue plaque recognising Eugene Aram’s impact on the town – and indeed, on society – in 2010, which can be found along the High Street.

Sources for this article include a blog post on the North Yorkshire County Records website, an article for King’s Lynn magazine, an article for Britannica.com, a blog post on the Norfolk Record Office website, Eugene Aram, A Tale by Edward Bulwer Lytton, 1891 via Project Gutenberg, Eugene Aram, His Life and Trial by Eric R. Watson 1913, and the Knaresborough Civic Society website.

0