Subscribe to trusted local news

If you are accessing this story via Facebook but you are a subscriber then you will be unable to access the story. Facebook wants you to stay and read in the app and your login details are not shared with Facebook. If you experience problems with accessing the news but have subscribed, please contact subscriptions@thestrayferret.co.uk. In a time of both misinformation and too much information, quality journalism is more crucial than ever. By subscribing, you can help us get the story right.

- Subscription costs less than £1 a week with an annual plan.

Already a subscriber? Log in here.

10

Nov 2024

The extraordinary story behind one of the names on Harrogate’s war memorial

This Sunday, to mark Remembrance Day, the Royal Air Force Association will hold a service and lay a wreath at Harrogate's war memorial, to commemorate the lives lost in the two World Wars, and in later conflicts.

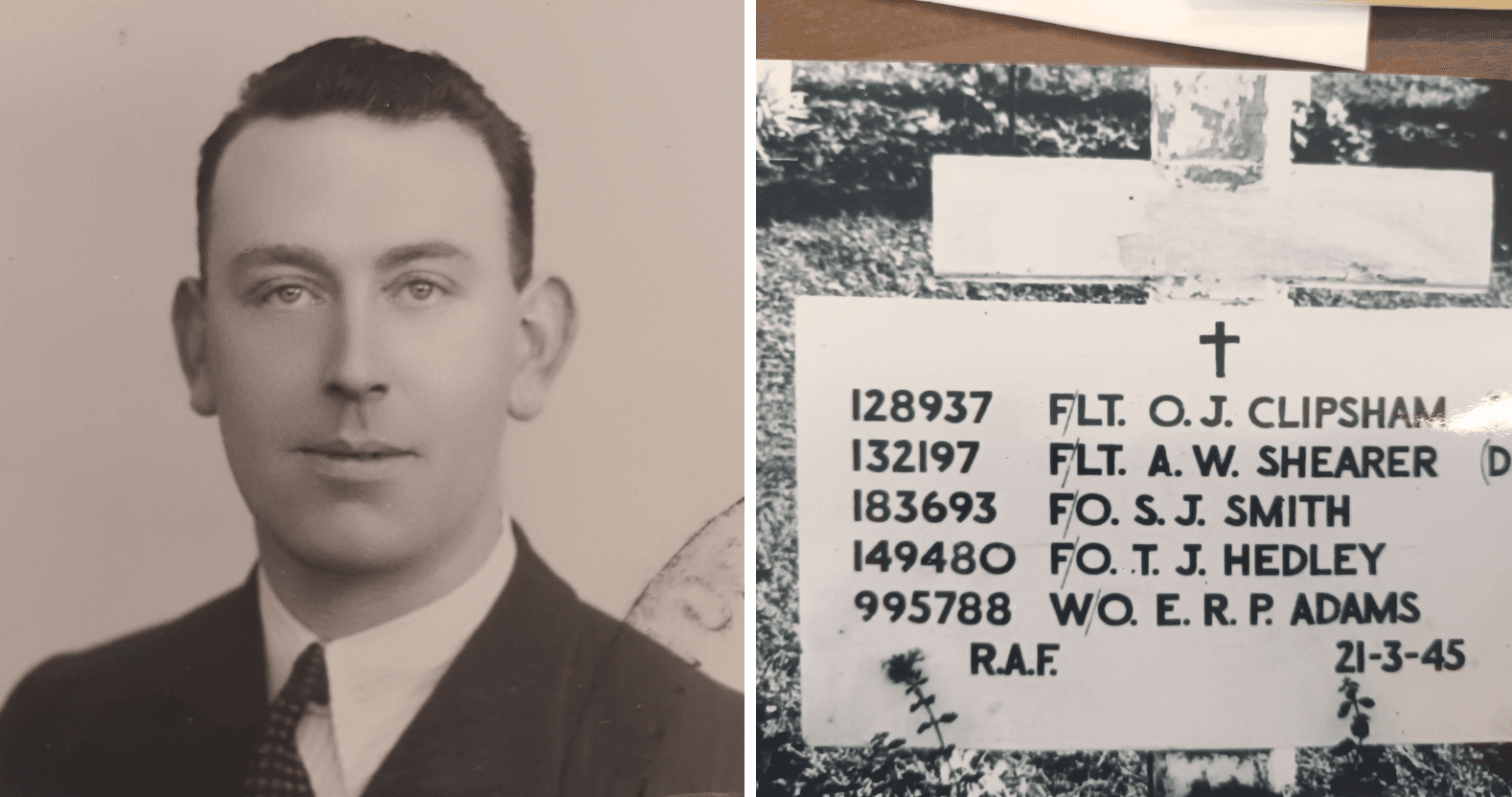

There are 1,163 fallen servicemen and women from the First and Second World War recognised on the memorial. One of these is a T.J Hedley – known as Thomas James Hedley, or Jim to his family. He was a flying officer in the RAF, and died on March 21, 1945, aged just 34 years old.

His story – and that of his squadron – is extraordinary, but tragic. And, if it wasn’t for one well-placed classified ad in the Harrogate Advertiser back in 1999 it could be a tale lost to time.

As his nephew David Finnegan explained:

These are the stories that are disappearing, unless they’re passed down the generations.

There are so few veterans who served in the war still around to tell their stories, so it’s up to us to keep them alive.

180 Squadron of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserves.

The fatal mission

In 1945, Hedley served in the 180 Squadron of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserves. On the morning of May 21, he boarded the Mitchell II FW236 bomber plane he served on.

The crew consisted of pilot Oliver Jack Clipsham, navigator Austen Whyte Shearer, and another wireless operator/air gunner Edwin Richard Philpot Adams.

That day, there was a late addition to the numbers; military photographer and Stuart Jack Smith, who had been destined to join another plane but, in a tragic twist, a mix-up had led him to boarding Clipsham’s plane instead.

A deeply held superstition at the time was that it was considered bad luck, even fatal, to accept an extra crewman. Despite this, Clipsham allowed Smith to join, and 180 Squadron's six planes took off from Brussels, at approximately 9.15am.

Each plane was carrying eight 500lb bombs, which were to be dropped 120 miles away, over Bocholt, in Germany. The target was railway marshalling yards, with the aim of cutting off supply lines across the country.

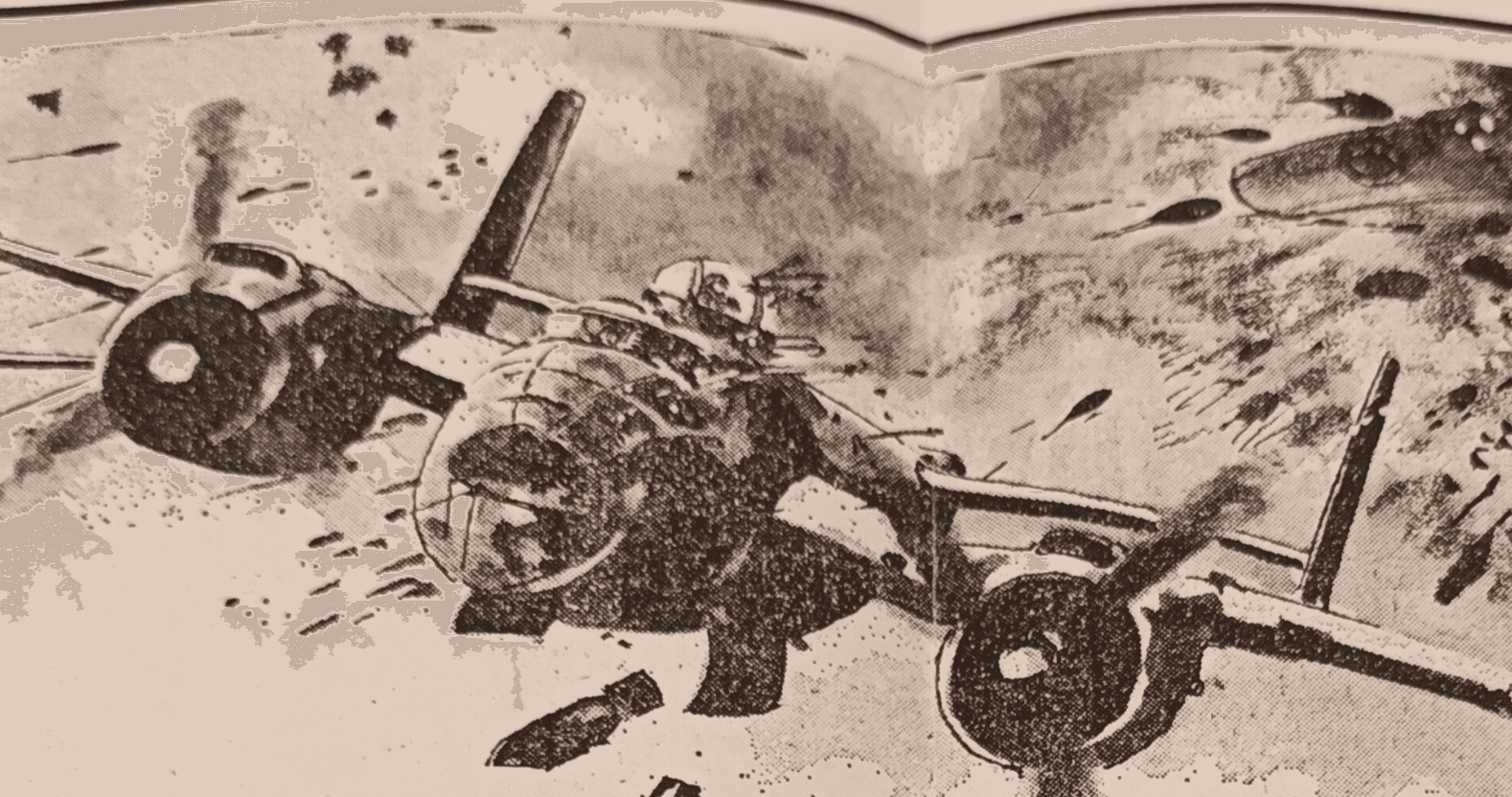

An illustration of a Mitchell bomber, as featured in a 1983 copy of The Sunday Express.

The planes were flying in formation when they experienced heavy flak. It is believed that during the barrage, the final bomb was jammed, unable to be dropped.

Simultaneously, flak may have entered Clipsham’s plane through the open bomb doors, and the bomb detonated, killing all on board instantly, scattering the debris across the German countryside.

The rest of the formation was rocked with the force of the explosion. Plane No.3 sustained catastrophic damage and crashed, killing Australian pilot Bobbie Kennard and his crew.

No.6, also flown by an Australian national, Tom Crowley, received damage to his plane’s nose, but managed to stay in the air.

Flanking Clipsham’s plane, No.4 also received the brunt of the explosion, seriously injuring its pilot Richard ‘Dick’ Perkins. Thanks to the heroic efforts of gunner Jim Hall, the plane was landed back in Allied territory, and all the crew were spared.

Escaping the enemy

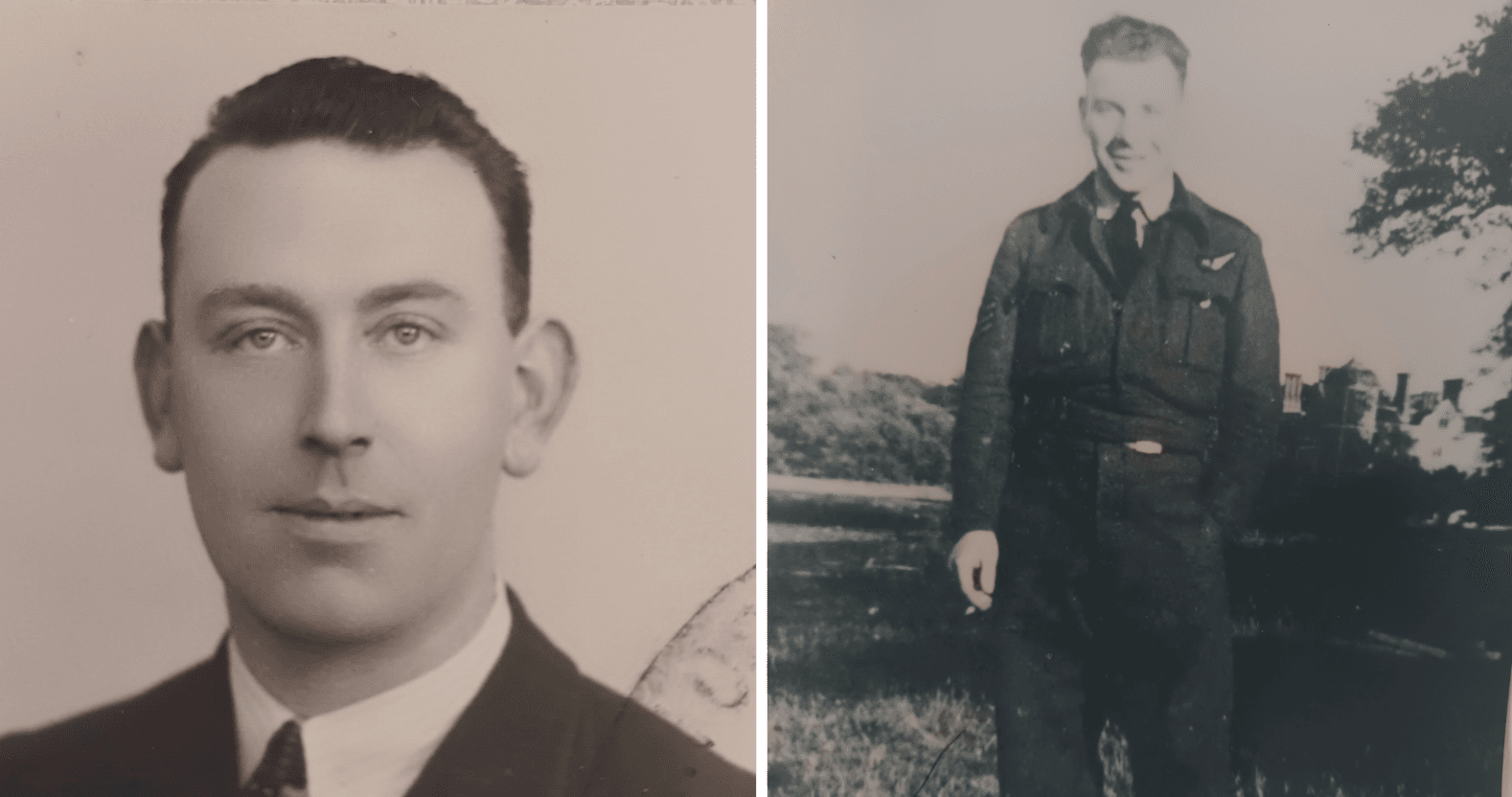

Thomas James Hedley was born in 1911 in Chester-le-Street, the eldest child of David Arthur and Margaret Ann Hedley. The family, including Hedley’s younger sisters Mary and Olive, moved to Harrogate in the 1920s.

Much of the information about Hedley’s time in service comes from Olive, David Finnegan’s mother, who has since passed away. She was a young woman at the time of her brother’s death, and sadly some details have been lost to time and memory.

One key story that she did tell David, adding a further layer to Hedley’s life is that earlier in the war, he’d escaped from German-occupied France with the help of the French Resistance, after his plane was shot down.

Once safely back behind Allied lines and reunited with his unit, he was granted compassionate leave and returned to his family.

(L) T.J Hedley (R) E.R.P Adams

Olive recalled that he was 'malnourished and covered in lice' and that their mother instructed the sisters to go outside while she helped Jim bathe. Food was rationed, but the family gave what little they had to build up his strength.

A photograph, believed to be taken around that time, shows a much slimmer Hedley with thinning hair and bad teeth, perhaps an indication of the trauma he’d been through; months of hiding with little food, on the run from enemy forces.

Although this is unconfirmed, Olive believed that due to his condition he might have been granted indefinite leave but chose to return to his squadron and continue fighting.

He rejoined in the closing stages of the war, playing a part in the push across the Rhine, to take more German territory – and sadly lost his life in the process.

Rediscovering the past

While David had grown up with Olive telling him stories about his uncle, it wasn’t until his attention was drawn to a classified advert in Harrogate Advertiser in 1999 that pieces of the puzzle began to fall into place.

The person who placed the advert was Russell Le Grosse from Tyneside– his uncle was E.R.P Adams, and he was trying to find old photographs and more information about the rest of the crew.

At first hesitant – David was caring for his mother at the time – he did eventually reach out, with Le Grosse coming to Harrogate to meet them both. From there, both parties could help to fill in the gaps in the timeline.

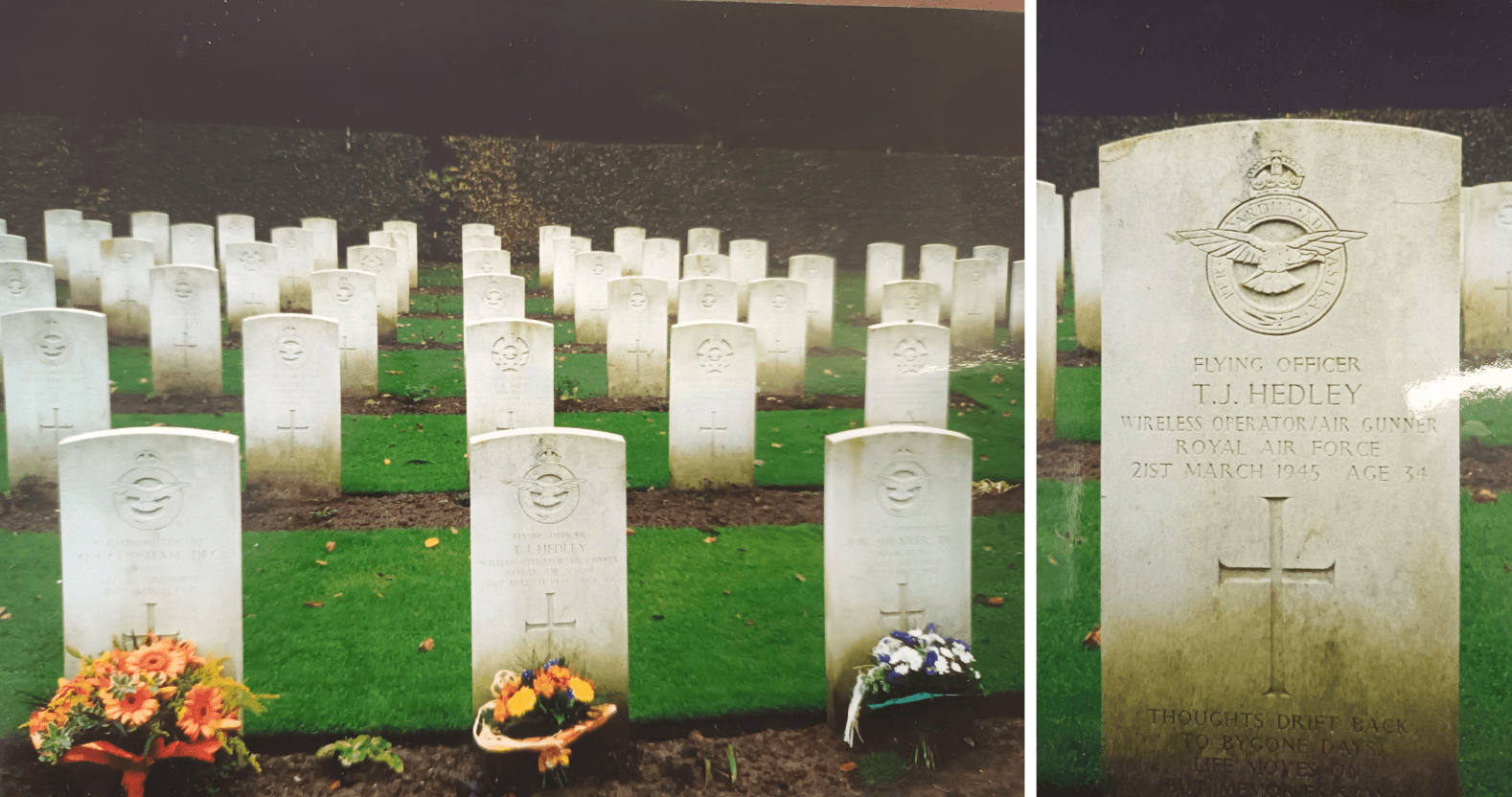

The graves in Reichswald Forest War Cemetery, Germany

Olive had never known the full details of her brother’s death, always believing that he had been shot down over The Black Forest. However, Le Grosse had discovered that Hedley, Clipsham and the crew had headstones in Reichswald Forest War Cemetery in Germany.

David said:

Russell had done the largest part of the research, because of his connection through his uncle.

He uncovered all of this information by writing to people and exchanging information. He’d discovered they [the crew] were actually buried in a communal grave, which is now an industrial area – there’s no marker there now.

He got a group together and they went over to visit the site and pay their respects.

David was unable to go, but as a lifelong resident of Harrogate, he’s able to visit the Harrogate war memorial to honour the uncle he never got a chance to meet.

Last year marked the 100th anniversary of the obelisk. To recognise the occasion, an exhibition was hosted at West Park United Reformed Church.

Called More than a Name on a Memorial, it drew heavily on research compiled by former army reservist Graham Roberts to look at the lives of those whose names are inscribed on the memorial.

For David, he has his own archive to remember T.J Hedley by; photos, newspaper clippings and his uncle's Bible, the orginal owner of which was his father and David's great-grandfather David Arthur, who died in WW1.

He added:

All of those people have a tale to tell but most of those stories are being lost and I don’t like that.

If things had been different and we hadn’t won the war, would Harrogate exist as it does now? I doubt it.

0