This article is written by Historian Malcolm Neesam. Malcolm is a much-published author. In 1996 Harrogate Borough Council awarded Malcolm the Freedom of the Borough for his services as the town’s historian.

This article is written by Historian Malcolm Neesam. Malcolm is a much-published author. In 1996 Harrogate Borough Council awarded Malcolm the Freedom of the Borough for his services as the town’s historian.

The rows about the effect on the Stray of the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) cycling event in 2019, and more recent proposals to construct cycle routes and extra outdoor space for bars, emphasise the high importance it has for many people.

This is nothing new, and modern readers may be interested to learn of one of the biggest rows in the history of 20th-century Harrogate which – as ever – was fought between the council and the public, with the result that the council was thrown out of office. Known as the “battle of the flowerbeds”, the issue achieved national press coverage.

It was in November 1932 that the council took up the suggestion of J G Besant, the parks superintendent, that the approaches to the town centre would be made more attractive by the construction of flower beds on West Park Stray between Otley Road and Montpellier Hill. The idea had come to Mr Besant while on holiday at another British resort, which had a similar feature.

Although this was a nice concept, Mr Besant did not seem to understand that the Stray did not belong to the council but was protected by Acts of Parliament for the main purpose of keeping its 220-odd acres intact and free from “incroachment” – any enclosure that hindered public access other than those allowed by the Acts, such as public lavatories.

It is a mystery why town clerk J Turner Taylor did not warn the council that the Besant proposal entailed a breach of the Harrogate Corporation Act 1893. Mr Turner Taylor, who was possibly the best town clerk or chief official ever to work for Harrogate, had come to office in 1897, the year of Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee, and worked devotedly for Harrogate, wearing himself out in the process. He had wanted to retire after the First World War, but remained in office at the urging of the council and by the 1930s was exhausted and also ill with the malady that would kill him barely a year after his 1935 retirement.

The 1893 Act, 56 & 57 Victoria, section 10, stated that the corporation “must keep the Stray unenclosed and unbuilt as an open space for the recreation and enjoyment of the public” , with section 11 adding “the Corporation shall at all times… preserve the natural aspect and state of the Stray… and protect the trees, shrubs, plants, turf and herbages growing on the same and shall prevent all persons from felling, cutting, lopping or injuring the same and from digging clay, loam and soil therefrom”.

As the proposed flowerbeds would require removing the surface herbage and disturbing the sub-soil, with the public subsequently being unable to use those areas, a breach of the Act was clear. But for whatever reason, Mr Taylor Turner never appears to have advised the council of this. On the contrary, on December 23 1932 the Yorkshire Post noted that not only had the clerk advised that the proposal was legal, but his opinion was backed by the chairman of the Stray Committee, the lawyer Mr S Barber. Consequently, the council’s pursuance of its parks superintendent’s scheme resulted in disaster.

One and a quarter acres of the Stray were dug up and turned into flowerbeds in 1933, to the anger of residents

Even before the council’s fateful decision, the owner and editor of the Harrogate Advertiser W H Breare wrote a blistering statement warning that the action was illegal. Nevertheless, at a full council meeting on December 12, approval was given to spend £40 on the preparation of the beds, and £70 on labour.

Work on clearing the Stray’s surface then began. The Besant plan called for two rows of variously shaped beds to be carved out between the junction of West Park and Otley Road. The outer row nearest to the highway consisted of 27 beds for flowers between Otley Road and Beech Grove, with a further row of 11 single beds for shrubs between Beech Grove and the footpath that ran from lower Montpellier Hill to Victoria Road and Esplanade.

In all, some one and a quarter acres were lost, with one third of the replacements being filled with shrubs, and two thirds with flowers, for which three plantings per annum were envisaged, requiring about 18,000 plants per planting.

Public reaction was instant and hostile, with strong opposition being expressed to individual councillors as well as to the press. One councillor, Mr J C Topham, tried to have the minutes of December 12 1932 rescinded on January 9 1933, but voting went against this with five in favour, and 20 against. The council now set itself to resist firmly the public opposition, but it miscalculated the degree of resentment towards its intransigence. The battle was only beginning.

Backed with increasing signs of public disquiet, at the February council meeting Cllr Topham introduced a further resolution to rescind the resolution of December 12. Again the resolution failed with five in favour, and 23 against – and the town clerk again stating that the Besant plan was legal.

At this second failure, public opinion exploded, and on February 9 one of the largest public gatherings ever held in Harrogate was held in the Spa Rooms, with the press reporting that hundreds of townspeople had to be turned away.

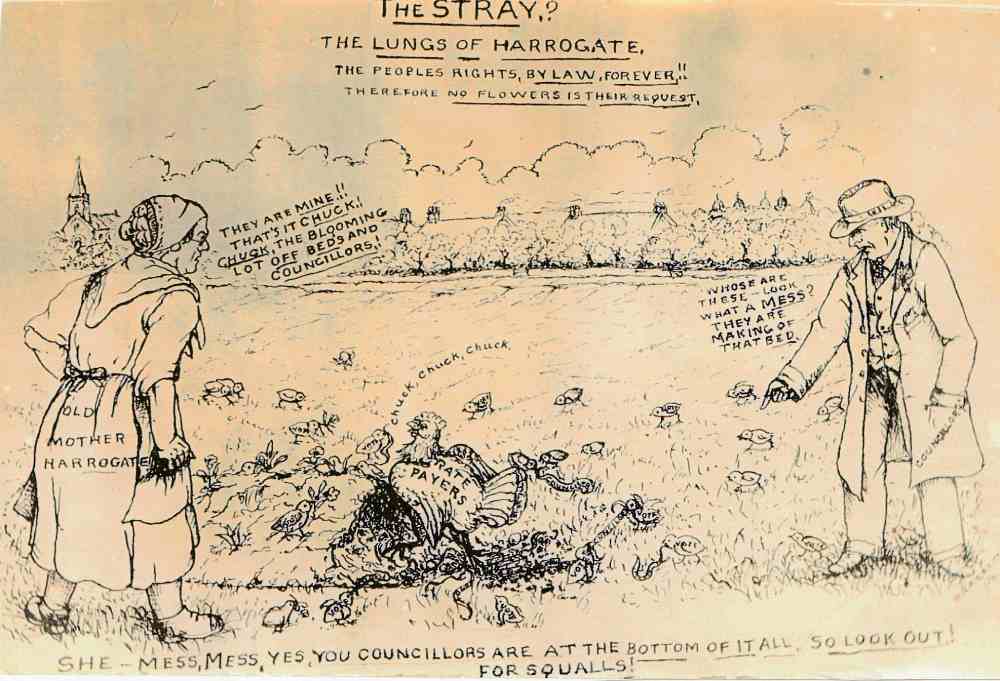

A satirical cartoon from 1934 shows Old Mother Harrogate haranguing councillors

This meeting, which was chaired by Mr Tyack Bake, included a reference to a 1923 scheme of the council to build 20 tennis courts on West Park Stray, which was abandoned after vociferous public protest. The meeting, which included several members of Harrogate’s legal profession, ended with resolutions to oppose the council’s scheme and to test its legality. A meeting held by the Chamber of Trade expressed similar reservations.

Public fury increased substantially when on May 8 1933 the council gave approval to the Stray Committee to remove 5,000 square yards of turf at Stray Rein for re-laying on the new terraces in Valley Gardens outside the Sun Pavilion. As the turf had already been removed, any objections were a bit late!

Residents of Beech Grove sent their butlers to protest outside the council’s new Crescent Gardens offices. Another wealthy resident threatening to drive his Rolls Royce over the illicit “inclosures”. But by far the greater number of protests came from less affluent members of Harrogate’s citizenry.

By spring 1933, it was clear to the public that the council would not be moved, and so the obvious solution was to remove the council instead. A new organisation, named the “Stray Defence Association” (SDA), was born. As the summer of 1933 progressed, and opinions hardened, the press – both regional and national – was filled with heated correspondence relating to Harrogate’s “Battle of the Flowerbeds”, whose supporters received a considerable boost from a remark attributed to the visiting Queen Mary that the new flowerbeds “looked very nice”.

Due to uncertainty over the legal situation because of a section of the 1893 Act, which empowered the corporation to plant trees and shrubs on the Stray, the new defence association decided not to embroil the town in an expensive legal wrangle, but to oppose at the coming November’s elections those councillors known to support the Besant plan. In September, the SDA sent councillors a letter stating its objective in restoring the Stray and asking for their support.

When in the majority of cases this was not forthcoming, the SDA resolved to stand for election against individual Stray desecration supporters. Mr R Ernest Wood and Arthur Pearson put their names forward. Both were returned as councillors.

With this success behind them, the SDA again asked to remove the beds, which was met with a curt refusal during the council meeting of January 8 1934. So many people tried to gain admission that the council was forced to move the proceedings to the Winter Gardens, where several outbursts of public anger drowned out councillors. However, the opponents of the Besant plan on the council had now increased from five to 12, one of whom was the youthful Harry Bolland, who showed his political sensitivity by admitting the council had got it wrong.

As for the 18 who still remained in support, the SDA announced they would be opposed by its members when the elections came around again later that year. In November 1934, all four association candidates were returned on the policy of restoring the Stray.

It was at a lively meeting on November 9, complete with interruptions and much booing from the public, that the new council debated whether to remove the Besant beds. The motion from Alderman Bolland that it be a matter of urgency that the Stray be restored was supported by 18 votes for against 13 die-hards who opposed it. The motion passed, and work began immediately to restore the Stray, with the sites laid down to grass.

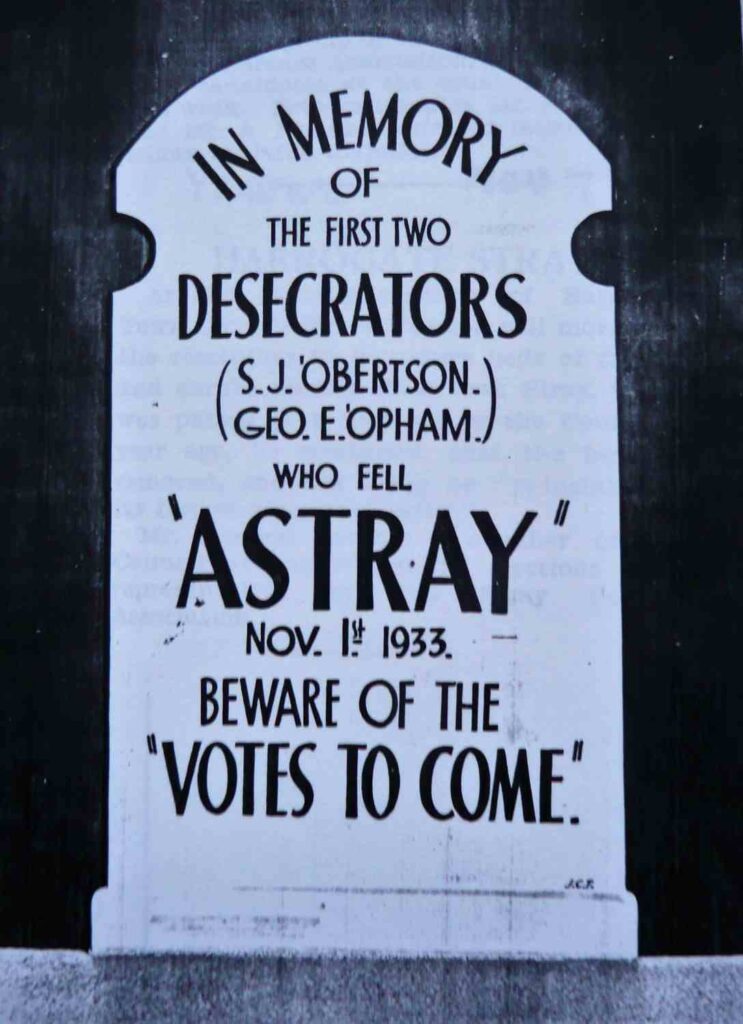

A mock tombstone for Harrogate councillors over the Stray flowerbeds battle in the 1930s.

Throughout the “battle of the flowerbeds”, a hard core of councillors remained oblivious to public feeling, the mayor in particular exhibiting a furious contempt towards his opponents. All this did nothing to maintain respect towards elected representatives. More dangerously, the sudden re-formation of the council on a one-issue basis (i.e. the restoration of the Stray) meant that the council faltered with its three-part plan for the Valley Gardens, until the issue of treatment accommodation at the Royal Baths became of pressing importance towards the end of the decade.

It has been because Harrogate’s history is not taught to councillors that the battle of the Stray has to be re-fought on average once a decade. Invariably, these are the result of the council attempting to foist on the public alterations to the Stray “for the good of the town” or to placate some noisy action group. Most dangerous of all is when the council decides some pet scheme requires new legislation to change the law prohibiting inclosure.

Some examples of these pressures were the suggestions to build tennis courts on the Stray in the 1920s, a boating lake in the 1930s, a hula-hoop park in the 1950s, a conference centre in the 1960s, or an underground car park in the 1970s. But the Stray has survived because the public wanted its Stray to remain untouched. Long may this be true.

Read More:

- History: Where is the vision, where is the hope?

- Council to recommend Wetherby Road land for Stray swap